Physician Compensation: Owners and Employees

September 22, 2017 | Featured Articles

When researching the biggest challenges faced by our clients (independent pediatric practices across the US) we invariably discover that at the top of the list sits Human Resources (HR). Initially, practices focus on staff problems – hiring and firing, how to manage a front desk, and other problems of this sort. When we push a little harder however, we almost always learn that a major source of discontent is how the physicians pay themselves. Let’s take a look at some lessons-learned and best practices for managing clinician compensation for both partners and employed clinicians.

PART 1 – Paying Employed Clinicians Fairly

At least once a month, we get a call or email from a practice that revolves around one of these consistent themes:

– “I can’t afford to hire a nurse practitioner.”

– “My practice is losing money even with my four employed docs.”

– “My employed pediatrician wants a raise.”

Each of these challenges is hinged to a simple math problem that too many practices fail to solve. Using insight gathered from a series of surveys PCC conducted with employed clinicians and the data from your practice can help you address each of the issues noted quickly and cleanly.

Lesson One: No Margin, No Mission

First, let’s make an important assumption: you expect to generate margin from your employees. That is, you don’t intend to subsidize physicians or nurse practitioners working for you. There are sometimes good reasons to do so, but they are nearly always temporary, and right now you need to focus on the long-term health of your practice and growing in a sustainable way.

As a result, we have to presume that you will make a profit from your employed clinicians. Profit is not a dirty word – profit is what allows your business to survive, allows you to continue to treat your patients, and allows you to employ your staff and clinicians. Without profit, your practice fails the moment your overhead increases. Profit is healthy and vital for both you and your patients.

At PCC, where we measure both clinical and financial benchmarks for our clients, we have identified a strong positive correlation between the two sides of the business. The practices with the strongest financial health are the ones delivering the greatest clinical response to their patients. This shouldn’t be a surprise – the discipline required to be successful is similar on both sides. Don’t be afraid to succeed.

So Lesson One: plan for financial as well as clinical success.

Lesson Two: It’s Not About the Money

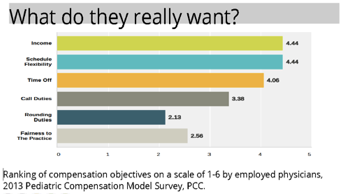

In a 2013 Pediatric Compensation Model survey conducted by PCC, we asked employed clinicians what the most important objectives were for their compensation. As you can see from the data in the provided graph, income is at the top of the list, ranking 4.4 out of a scale of 6. Note however, that tied with income is “Schedule Flexibility”, followed closely by “Time Off.” In fact, 4 of the top 6 objectives for employed clinicians target non-financial goals, namely, lifestyle/schedule goals. This is vital for understanding the relationship you have with your employed clinicians, especially younger ones. When you offer a full-time package to a newer clinician, especially one who has or is contemplating having a family soon, he or she is likely to demand significantly more to lose flexibility. Consider working with clinicians who might cover times you don’t presently serve well (after 5pm or weekends), and consider having multiple part-time clinicians instead of a single full-time doctor.

Many practices report to us that younger physicians, after working part-time through their children’s school-years, suddenly wake up to wanting to work full-time or become partners. Having the opportunity to work with someone for a few years before deciding if you want to take on a new partner, or pass the practice along, is an invaluable opportunity!

You may well have a vision for what you need for additional clinical service in your practice. For many readers here, it’s about sharing the burden of the practice or perhaps even being able to take some time off. Consider the talent pool from which you are hiring and realize that FT work may not be a good match – adjust to your market and you may be rewarded.

Lesson 3: Do the Math

Unfortunately, this is where most practices stumble, but the lesson is simple:

Your employed clinicians need to generate enough revenue to cover their expenses, their share of the overhead, and your margin.

That’s it. There’s no magic or science involved, but you will need to do a little homework about your practice revenue to speak to the issue of employed clinicians clearly. The three pieces of information you need to gather are:

- The expected revenue-per-visit of your clinician

- The expected visit volume for your clinician

- Your practice overhead (defined as your total expenses divided by your total revenue, without direct clinician expenses like salary)

Use your existing practice data as a baseline estimate and then adjust for the expected potential differences (a new clinician may not have a full schedule initially or a new clinician may have a different visit profile). There are different methods to approach the math, but the most common involve starting with a salary and calculating the required revenue OR estimating the expected revenue and then calculating the maximum salary. Let’s look at an example of each.

Example A: You want to hire a new pediatrician and she expects to make $150,000

First, you need to convert her $150,000 into a reasonable estimate for what the practice needs to generate to cover her expense. If she expects to earn $150,000, we know that the additional employer tax and other benefits will push the full figure to as much as $175,000 (adjust as appropriate) – too many practices fail to account for the real cost of their employed physicians!

Next, you need to account for the general practice overhead (let’s say 60%) and a realistic margin (let’s say 10%). If overhead plus margin is 70%, the remaining 30% of revenue will be needed to cover the $175,000 estimate above. You can quickly see that in order to earn $175,000 in salary and benefits without the practice subsidizing the employee, she will have to generate $583,000.

Note: you are, indeed, presuming that the practice overhead will remain fixed even with the addition of significant revenue from the new employee. It’s certainly true, on paper, that your overhead should decrease with additional sources of revenue, given the fixed costs of running your practice (particularly rent and most staff time). If you are sophisticated enough to properly account for the correct overhead, excellent! As a practical matter, expect your overhead to drop, but not substantially – 20 physician practices hover around 65% overhead, as do 2-physician practices.

Once you know that she needs to generate $583,000, apply your revenue-per-visit to the result. If you generate $125/visit, and don’t expect her visit profile to differ, then you know she’ll need to see just under 4,700 visits over the course of the year. If she wants to work only 3 days a week, that’s 31 visits/day – a number that few new clinicians can generate.

You can quickly see how many practices end up losing money on their employed clinicians! In order for this example to make sense to the practice, we need to either lower the salary expectations of the physicians, increase the volume or revenue-per-visit contribution of the clinician, or be prepared to subsidize the employee.

Example B: Your employed clinician has asked for a raise

When we start from the other end of the equation – with known productivity numbers – the offers can become more concrete. Let’s say you’ve employed a part-time NP for the last few years and now that her kids are in high school, she wants to work more and increase her salary. Use actual practice data to quickly figure out what you can do to accommodate this request.

- Present Salary and benefits: $75,000

- Revenue-per-visit: $135

- Total Revenue: $375,000

- Practice Overhead: 65%

Quick math here shows that, after accounting for practice overhead, there is $131,000 left from her revenue to cover your margin and her cost. Subtracting $75,000 from $131,000 leaves you with $56,000 or approximately 15% margin, which is very reasonable for both parties.

Now that she is willing to increase her visit volume, you know that at least 35% of the additional revenue will be left over (perhaps more as your revenue increases – see above). You can determine how much of this revenue you wish to share – you could continue to keep 15% and mutually project that she can keep 20% of all the additional revenue . . . and feel confident that you are making a financially sound decision based on evaluation of the data.

Part 2 – Paying Physician-Owners Fairly

“The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second-best time is today.” Although apocryphally a Chinese proverb, it sure sounds like it came from a managing partner in a medical practice.

One of the biggest holes in the practice management landscape is partner compensation. The challenges come from many directions – senior partners declaring “No more call!” without a change in compensation, disgruntled physicians who feel that the distribution isn’t fair, or perhaps the receipt of a big P4P check and disagreements on how to split it up. Through the execution of three national surveys of independent pediatric practices, and years of work with practices on their compensation models, PCC has learned what the practices with the most compensation satisfaction can share, and what we can learn from them.

The most common problem practices seek to solve is how to be “fair.” There are three predominant models used by practices to distribute money fairly:

- Pure productivity (or “Eat What You Kill”)

- Equal distribution

- A combination of the previous two

There are pros and cons to each method and digging deeply into offices using each has turned up some valuable insight. Primarily this: there Is no magic compensation model.

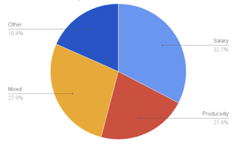

Detailed interviews and consecutive surveys failed to tease out any evidence that there is a particular partner compensation model loved by all. There are very satisfied practices that split every penny evenly, just as there are practices that detail every expense in order to assign them to a physician. For example, the three models are fairly evenly split in the wild, which suggests that conventional wisdom hasn’t identified a best practice. In the 2013 study of compensation models, 32.7% were based on salary, 21.4% were based on productivity, 27.6% had a mixed compensation model, and 18.4% based their models on another method of disbursement. Older practices with more experience do not exhibit any patterns nor do new practices, started by physicians dissatisfied with their previous employers or partners. In other words, the market hasn’t identified the best method for distributing income to partners.

One pattern is worth mentioning, however- practices who use some measure of productivity are more likely to be satisfied. The data shows that the introduction of any recognition to the bottom line, no matter how small or significant, creates some understanding of “fair” in most practices. Again, this isn’t a universal truth – there are plenty of satisfied “equal pie slice” practices, yet practices with some measure of productivity are a little more likely to be satisfied.

2013 PCC Survey of Compensation Models

Productivity Measure Doesn’t Matter

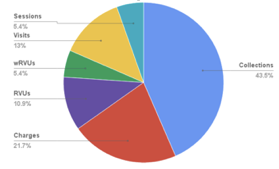

In my work with practices, when determining what measures to use for a productivity model I often get asked, “Should I use Work RVUs or RVUs or charges or payments?” Repeated review and analysis of the various productivity measures makes it clear: it doesn’t matter what measure you use, as long as the physicians understand the measure, it’s easily and transparently calculated, and doesn’t penalize a physician with a unique panel (high Medicaid, all newborns). This shouldn’t come as a surprise – in an evenly distributed practice, the correlation among charges, payments, RVUs, wRVUs, and even visits, should be remarkably tight. If those measures are not highly correlated, then something interesting is happening in your practice that you’ll need to evaluate moving forward.

One important piece of advice: share the data clearly and cleanly. Too often, a repeated narrative (“I am the busiest doctor here!”) becomes “truth” even if it’s not demonstrably true. Nothing will settle an argument faster than pointing out that each of the physicians is, in fact, within a 5% productivity range.

2013 PCC Survey of Compensation Models, Productivity Measures

Recognize Non-Clinical Work

One of the biggest sources of contempt in the practices we work with is the lack of recognition for non-clinical work. When one clinician feels like she “does all the work”, resentment will invariably build. In some practices, the distribution of non-clinical work is managed in a reasonable, unspoken way and the parties are relatively satisfied. More often however, the important work of running the practice is not evenly distributed, and there are many who are blissfully unaware of the work being done for them. Our 2013 survey uncovered that:

- 58% of practices pay physicians for non-clinical duties (administration)

- For those who pay for non-clinical duties:

- 70% pay for being Managing Director

- 17% pay for negotiating work

- 30% pay for clinical projects

- 15% pay for HR work

- 26% pay for IT work

- 20% pay for being Medical Director

- 11% pay for external professional work

- 25% pay for other things as well

- Almost none use other measurements for incentives (patient satisfaction, peer review, community outreach, etc.)

There is no best-practice for how to value non-clinical work. Again, simply assigning *some* value to the work provides the greatest tension relief. Most physicians just want to have their work valued and recognized – it’s not simply about the money.

A common task we recommend for practices confronting this challenge is to ask every partner to simply track the time they spend doing non-clinical work for a few weeks. Inevitably, one of two things happens: the group discovers that one person truly is doing all the practice management work or that the work is actually spread out more than is initially understood. Either result will lead to a better understanding of how to compensate that clinician.

Consider Partner Symbiosis

One of the flaws of the productivity measures above is that they are each ultimately volume based. If you see more patients, you have more revenue/charges/RVUs. A common misconception held by many of the “most productive” partners in many groups is that their individual productivity is somehow independent from the other work done in the practice. Tell-tale anecdotal comments include, “Well, she takes so long with all those teen visits,” or, “I bring in all the new families and see 30 kids a day while he only sees 15.”

Very often, the ability to be the most productive clinician depends wholly on other clinicians peeling off the visits that would otherwise hinder that productivity. That “slow” doctor who spends all the time with the teenagers? Without her, those appointments would be pushed into the schedule of the “busy” doctors, zapping their high volume. Worse, when a family can’t find a good fit in your practice any more – perhaps because your “producers” don’t want to deal with asthma or obesity or eating disorders – they will take their business out of your office. When considering productivity, think about how each clinician might fare in solo practice. It’s very likely that a few different styles and speeds in an office benefits everybody.

Should You Be Partners?

Often, as we excavate an outdated 30-year-old compensation model and review comments from each of the partners about what they like and don’t like about it, we have to ask them: “Why are you partners?”

We can’t stress this enough: there is no perfect compensation model that recognizes the entire contribution of each partner. And if money is the focus of your partnership, there will always be a struggle. Ultimately, you need a core philosophical agreement about how the partnership should pay the owners. If three of you want full productivity and two of you just want to “split it,” be prepared to argue forever. If your partners don’t want to pay for all of your practice management efforts, but you’re sick of not being recognized for doing it, why are you partnered with them? In fact, if a partner is only interested in the give/take relationship between revenue/expenses and not contributing to the management of the practice in some way, why are you partnered at all? Partners are the ones taking risk, losing sleep, and doing the work beyond the exam room – and they should be paid for it when the practice succeeds. If someone just wants to see patients and go home, the relationship should probably be redefined.

In other words, a “compensation model” problem is often, in fact, a partnership problem.

Now is the Best Time to Plant the Tree

Returning to our proverb, when is the best time to work on your compensation model? The answer is always TODAY. Even, and perhaps especially, if people are currently satisfied all around. When everyone is happy, it’s the easiest and least contentious time to consider making changes. Waiting for someone to express discontent or anger at your existing model will color the process and take longer to resolve. At the next opportunity, sit down with your partners and compare your productivity measures to your compensation, review your non-clinical compensation and ask each partner: is this working for us? If it’s not, get out the shovel and plant the tree.